Warning: Default sort key "{{{sortkey}}}" overrides earlier default sort key "Belford, Christine".

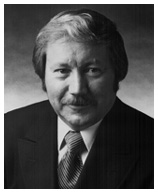

Glen A. Larson (3 January 1937 – 14 November 2014) was the creator of the original Battlestar Galactica and a consulting producer for the 2003 Re-imagined Series.

Larson was a prolific television producer and writer who created numerous iconic series throughout his career, including Knight Rider, Magnum, P.I., Quincy, M.E., and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century. His work consistently featured high-concept science fiction and action-adventure themes, often incorporating cutting-edge technology and vehicles as central elements of the storytelling.

As child to a single mother, Glen A. Larson would be later described as a "latchkey kid" by his son, David Larson, who notes his father's predilection for running water as being a means to remind himself of the halcyon time in his childhood. This was because Glen A. Larson's mother would start running a bath upon returning from work at night, and thus Larson would know that she had returned.[production 1]

Later in life as a young man, he became a page at NBC, where he became surrounded by motion picture and, later, television production.[production 2] During this time, he also entered the music industry under The Four Preps in the late 1950s, writing and performing songs that hit the top 5 in the Billboard pop charts, including "26 Miles (Santa Catalina)"[external 1] and "Big Man." In 1959, Larson appeared in the film Gidget, making it his first on-screen appearance.

During his work with the Four Preps, Glen A. Larson began writing using IBM Selectric typewriters, writing his first script called "Finger Popper," a script that was never produced.[production 3]

When it came to writing, Larson believed that "writing isn't writing, it's rewriting" during the search for themes of a story. Whenever he would come across a story problem, he would "reverse it"—"if you can't make something happen one way you look at the opposite [ways]."[development 1]

He was also known for isolating himself from distractions, secluding himself in his Malibu, California residence when writing, not answering phone calls and delegating tasks to others.[development 2] Jeff Freilich, Chris Bunch, and Alan Cole, among others, have noted this approach in various interviews relating to Larson's working methods.

Larson's television career began in earnest during the late 1960s, starting with associate producer roles on series such as It Takes a Thief in 1968. He quickly moved into executive producer positions, notably with The Six Million Dollar Man television movies in 1973, which established his reputation for high-concept action-adventure programming.

Larson's approach to science fiction television consistently emphasized accessibility and entertainment value over hard science fiction concepts. He believed in creating shows that would appeal to broad audiences while incorporating fantastical elements that captured viewers' imaginations. This philosophy became evident in his most famous creation, Battlestar Galactica, which combined space opera elements with family drama and military action.

According to the Official Companion, Larson wanted a credit for the new 2003 Miniseries by Ronald D. Moore who began the Re-imagined Series, and his claim went to arbitration at the Writer's Guild of America. Ron Moore actually felt that Larson deserved a credit because the story was essentially the same as Larson's, just done "in different ways". As a result, Larson is credited in the Miniseries under the pseudonym "Christopher Eric James."[production 4] Larson is also credited as a consulting producer on every episode of the Re-imagined Series because he holds the rights to the concept of Battlestar Galactica.

- It Takes a Thief (1968) (TV series) (associate producer)

- The Six Million Dollar Man: Wine, Women and War (1973) (TV movie) (executive producer)

- The Six Million Dollar Man: Solid Gold Kidnapping (1973) (TV movie) (executive producer)

- Quincy, M.E. (1976) (TV series) (executive producer)

- Battlestar Galactica (1978)

- Buck Rogers in the 25th Century Movie and TV series (1979)

- Galactica 1980 (1980)

- Magnum, P.I. (1980)

- Knight Rider (1982)

- Team Knight Rider (1997) TV Series (executive producer)

- Millennium Man (1999) (TV) (executive producer)

- Battlestar Galactica (2003) TV Miniseries (consulting producer)

- Battlestar Galactica (2004) TV Series (consulting producer)

- Caprica (2009) TV Series (consulting producer)

- Our point was to whenever possible make it a departure like you're visiting somewhere else and we did coin certain phrases for use in expletive situations, but we tried to carry that over into a lot of other stuff, even push brooms and the coin of the realm.[commentary 1]

Glen A. Larson died on 14 November 2014, leaving behind a significant legacy in television production. His influence on science fiction television, particularly through Battlestar Galactica, continues through both the enduring popularity of the original series and the successful re-imagined series that followed. His approach to high-concept television programming established templates that continue to influence producers and creators in the genre.

- ↑ Altman, Mark A.; Gross, Edward (2018). So Say We All: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Battlestar Galactica. Tor Books. ISBN 9781250128942, p. 34.

- ↑ Altman, Mark A.; Gross, Edward (2018). So Say We All: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Battlestar Galactica. Tor Books. ISBN 9781250128942, p. 36.

- ↑ Altman, Mark A.; Gross, Edward (2018). So Say We All: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Battlestar Galactica. Tor Books. ISBN 9781250128942, p. 35.

- ↑ Altman, Mark A.; Gross, Edward (2018). So Say We All: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Battlestar Galactica. Tor Books. ISBN 9781250128942, p. 35.

- ↑ Altman, Mark A.; Gross, Edward (2018). So Say We All: The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of Battlestar Galactica. Tor Books. ISBN 9781250128942, p. 35.

- ↑ David Bassom (2005). Battlestar Galactica: The Official Companion. Titan Books.

Christopher Golden (born July 15, 1967) is an American author of horror, fantasy, and suspense novels who co-authored two of Richard Hatch's Battlestar Galactica novels, Armageddon (1997) and Warhawk (1998).[external 1][external 2] The novels were part of a larger series of seven tie-in novels that Hatch wrote with various co-authors, representing a continuation of the Original Series, set twenty years after its conclusion.[external 3]

Golden was born and raised in Massachusetts.[commentary 1] He graduated from Tufts University in 1989 with a double major in English and history and a concentration in classics.[commentary 2] Golden is a third-generation Tufts alumnus and was a writer for The Tufts Daily during his freshman and sophomore years, where he reviewed films, books, and shows in Boston.[commentary 3]

During his time at Tufts, Golden took classes with influential professors including Jay Cantor's creative writing class in his first year and studied English and creative writing with Alan Lebowitz throughout his college career.[commentary 4] While at Tufts, he began shifting his aspirations from film school toward writing and the horror genre, noting that while his classmates wanted to write about social issues, he "wanted to write about zombies marching on Washington."[commentary 5]

Golden recalls that it wasn't until his senior year at university that he realized he wanted to write novels for a living. He experienced an epiphany in which he understood that if he could write twenty short stories, there was no reason he couldn't write twenty chapters of a novel.[commentary 6] In his senior year, Golden began writing his first novel, originally called Shadow Time, in Stratton Hall at Tufts in the fall of 1988.[commentary 7]

In 1989, Golden attended his first major writers' convention, where he met the woman who would become his literary agent for the next twelve years, as well as the editor who would buy both his first non-fiction book and his first novel.[commentary 8]

Golden's first published book was a non-fiction pop-culture project titled Cut!: Horror Writers on Horror Film, which he sold in 1990 or 1991 and was published by Berkley in 1992.[commentary 9] The book won the Bram Stoker Award in 1992.[commentary 10]

In 1992, at the age of 25, he sold his first novel. In that same year, Golden's agent sent editor Ginjer Buchanan the first 125 pages of the novel he was working on, and on the strength of that material, Buchanan offered him a two-book deal at Berkley.[commentary 11] Following this success, Golden quit his job at Billboard magazine in New York and moved back to Massachusetts with his wife to write full time, a decision he has never regretted.[commentary 12]

Golden's first novel, Of Saints and Shadows, was published by Berkley in 1994.[commentary 13] This was the first novel he had ever attempted to write.[commentary 14] The novel inaugurated his Shadow Saga series of urban fantasies centering on the vampiric hero Peter Octavian.[commentary 15] Golden's work on this novel has been recognized as influential in the development of the modern urban fantasy genre, with author Charlaine Harris noting that many elements fundamental to urban fantasy first appeared in the book.[commentary 16]

Golden has won the Bram Stoker Award twice, including for his novel Ararat in 2017.[commentary 17] He has been nominated for the Bram Stoker Award ten times in eight different categories.[commentary 18] In 2020, he won the Shirley Jackson Award along with James A. Moore for their anthology The Twisted Book of Shadows.[commentary 19]

Golden has frequently collaborated with other writers throughout his career, explaining that "writing is a solitary business and I'm not a solitary person."[commentary 20] He notes that conversations with writer friends often lead to collaborative projects when someone says "we should write that" about a crazy idea.[commentary 21]

With Mike Mignola, he co-created The Outerverse, a comic book universe that includes such series as Baltimore, Joe Golem: Occult Detective, and Lady Baltimore.[commentary 22] The character of Lord Baltimore first appeared in the novel Baltimore, or The Steadfast Tin Soldier and The Vampire, co-written by Golden and Mignola. Golden explained that while the initial plan was only for the novel, conversations during the development of a Hollywood version led them to realize there were many adventures to be told in the missing years from the novel, eventually resulting in the comic book series.[commentary 23] Golden describes Baltimore as "certainly the best thing I've ever done in the medium" of comics.[commentary 24]

He has worked with Tim Lebbon on several projects, including The Secret Journeys of Jack London series and The Hidden Cities series.[external 4] He collaborated with Amber Benson on the online animated series Ghosts of Albion, as well as related novels.[commentary 25] Golden and Benson have known each other and worked together for over twenty years.[commentary 26] Most recently, they co-wrote the Audible Original Podcast Slayers: A Buffyverse Story, which reunited the cast from Buffy the Vampire Slayer.[commentary 27]

Golden is well known for his extensive work in media tie-in novels. He has written or co-written numerous novels in the Buffy the Vampire Slayer universe, including Halloween Rain, Blooded, Child of the Hunt, The Gatekeeper trilogy, Immortal, Sins of the Father, Spike and Dru: Pretty Maids All in a Row, The Lost Slayer series, Oz: Into the Wild, Wisdom of War, and Monster Island.[external 5] Many of these Buffy novels were co-authored with Nancy Holder.[external 6]

Golden has spoken about his approach to working in shared worlds, noting that part of the satisfaction comes from "being able to play with characters you already love, to be the one putting the words in their mouths."[commentary 28] When working on Buffy novels, he tried to push the parameters of what was allowed, writing the first original Buffy novel, the first hardcover, the first trilogy, the first serial, and the first novel that didn't have Buffy in it—a World War II-era novel featuring Spike and Drusilla as protagonists.[commentary 29]

Golden also wrote Uncharted: The Fourth Labyrinth, a tie-in novel to the popular video game franchise. He explained that he only accepts media tie-in work when the passion is present, stating "If the passion isn't there, it just isn't worth it."[commentary 30] He noted that he did extensive research for the Uncharted novel, likely more than for any other book he'd written, covering topics including Ecuador, Incas, alchemy, Egypt, China, Daedalus, Atlantis, and labyrinths.[commentary 31]

His collaboration with Richard Hatch on the Battlestar Galactica novels Armageddon and Warhawk represented a continuation of the original 1978 series, set twenty years after the final episode.[external 3]

As an editor, Golden has worked on numerous short story anthologies including The New Dead, British Invasion, Dark Cities, Hex Life, Seize the Night, and Dark Duets.[commentary 32] He co-authored The Complete Stephen King Universe: A Guide to the Worlds of Stephen King with Stanley Wiater and Hank Wagner.[commentary 33]

Most recently, he co-edited The End of the World As We Know It with Brian Keene, an anthology of stories set in the world of Stephen King's The Stand.[commentary 34] Golden explained that receiving Stephen King's approval email was "such a gift" and that "The Stand is part of the foundation of who I am as a writer and as a human being."[commentary 35]

Golden has cited Stephen King as a major influence, describing King as "the narrative voice of my youth."[commentary 36] He has spoken about how King's work led him to discover an entire generation of horror writers and influenced his path to becoming a writer himself, going from reading S.E. Hinton and Doc Savage to The Stand and then "everything else."[commentary 37] Golden has named The Stand and John Irving's A Prayer for Owen Meany as his favorite novels.[commentary 38]

Golden grew up loving short stories, particularly those in anthologies edited by Charles L. Grant and Stephen King's collection Night Shift, before going backwards to read collections by H.P. Lovecraft and Edgar Allan Poe.[commentary 39] He recalls that his introduction to genre fiction came from watching The Twilight Zone and Kolchak the Night Stalker on television, and reading comics like Tomb of Dracula and Werewolf by Night.[commentary 40]

Golden has also expressed his lifelong love of collaborative writing, citing King and Peter Straub's collaboration on The Talisman as a formative influence. He recalled, "They were my two favorite writers and they were writing a novel together! How could it be anything but brilliant?"[commentary 41] John Skipp and Craig Spector's novel The Light at the End provided the inspiration he needed to finally start writing his first novel.[commentary 42]

Within urban fantasy, Golden has been influenced by what he considers the older definition of the genre, particularly the works of Charles de Lint, Emma Bull, and Tim Powers.[commentary 43] He noted that de Lint "has been a huge influence for me and is one of my favourite writers."[commentary 44]

Writing Process and Professional Activities

edit source

Golden typically works five to six days a week, sometimes seven. Most mornings are consumed by emails and business matters, with the bulk of his writing occurring just before lunch and throughout the afternoon.[commentary 45] He nearly always has music playing while writing, noting he could "literally listen to my iTunes for three weeks and not repeat a song."[commentary 46] When under deadline pressure, he sometimes works entire weekends, though he feels guilty about neglecting his family during these periods.[commentary 47]

Regarding his approach to writing novels versus comics, Golden explained that while the medium is totally different, his approach doesn't change much. He noted that it was only around the time he and Tom Sniegoski wrote Talent that he felt he "sort of figured the comics medium out."[commentary 48] If forced to choose between writing novels and comics, Golden would choose novels, explaining that "writing a novel doesn't require anyone else to bring it to fruition or to make it work."[commentary 49]

Golden is the founder of the Merrimack Valley Halloween Book Festival, which he established in 2015.[commentary 50] He is co-host of the podcast Defenders Dialogue with horror author Brian Keene.[commentary 51] He is a frequent speaker at conferences, schools, and libraries.[commentary 52]

Golden leads River City Writers, a company offering book and writing-related events, workshops in all areas of writing and publishing, focused writing retreats, and editorial and consultation services.[commentary 53]

Golden also teaches a writing workshop to seventh and eighth graders from his daughter's school, and he spent several years directing junior high musical theatre, which he misses and wishes he had more time for.[commentary 54]

Golden continues to live in Massachusetts with his family, where he was born and raised.[commentary 55] His son, Nicholas Golden, was a managing editor for The Tufts Daily in spring 2016.[commentary 56] He has been married to his wife for over 17 years as of 2008, and they have three children.[commentary 57]

Golden describes himself as a "TV addict who loves music, musical theatre, movies and ice cream."[commentary 58] His original novels have been published in more than fourteen languages in countries around the world.[commentary 59]

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Christopher Golden talks time at Tufts, writing inspirations (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). The Tufts Daily (February 12, 2018). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Tufts alumnus and best-selling author Christopher Golden talks writing with the Daily (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). The Tufts Daily (February 23, 2017). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Christopher Golden talks time at Tufts, writing inspirations (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). The Tufts Daily (February 12, 2018). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Christopher Golden talks time at Tufts, writing inspirations (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). The Tufts Daily (February 12, 2018). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: In Conversation With Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Alternative Magazine Online (December 28, 2011). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Christopher Golden talks time at Tufts, writing inspirations (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). The Tufts Daily (February 12, 2018). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Interview: Christopher Golden on Soulless (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Cynthia Leitich Smith (January 4, 2019). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Interview: Christopher Golden on Soulless (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Cynthia Leitich Smith (January 4, 2019). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Interview: Christopher Golden on Soulless (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Cynthia Leitich Smith (January 4, 2019). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Interview: Christopher Golden on Soulless (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Cynthia Leitich Smith (January 4, 2019). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Interview: Christopher Golden on Soulless (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Cynthia Leitich Smith (January 4, 2019). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Nightmare Magazine (January 22, 2014). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Interview: Christopher Golden on Soulless (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Cynthia Leitich Smith (January 4, 2019). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Nightmare Magazine (January 22, 2014). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Nightmare Magazine (January 22, 2014). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (Author of All Hallows) (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Goodreads. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden interviewed (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Alchemy Press (December 27, 2013). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden interviewed (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Alchemy Press (December 27, 2013). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Exclusive: Christopher Golden Talks Baltimore, Vampires, Mike Mignola And More (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Biff Bam Pop (July 5, 2012). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Exclusive: Christopher Golden Talks Baltimore, Vampires, Mike Mignola And More (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Biff Bam Pop (July 5, 2012). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Amber Benson and Christopher Golden Talk New Versions of Cordelia and Tara in 'Slayers: A Buffyverse Story' (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Tell-Tale TV (October 2023). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Amber Benson and Christopher Golden Talk New Versions of Cordelia and Tara in 'Slayers: A Buffyverse Story' (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Tell-Tale TV (October 2023). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Exclusive: Christopher Golden Talks Baltimore, Vampires, Mike Mignola And More (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Biff Bam Pop (July 5, 2012). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Exclusive: Christopher Golden Talks Baltimore, Vampires, Mike Mignola And More (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Biff Bam Pop (July 5, 2012). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: In Conversation With Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Alternative Magazine Online (December 28, 2011). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: In Conversation With Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Alternative Magazine Online (December 28, 2011). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Nightmare Magazine (January 22, 2014). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Editors Christopher Golden and Brian Keene and anthology contributors (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Grimdark Magazine. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Editors Christopher Golden and Brian Keene and anthology contributors (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Grimdark Magazine. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Nightmare Magazine (January 22, 2014). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Nightmare Magazine (January 22, 2014). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Nightmare Magazine (January 22, 2014). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ An Interview with Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Civilian Reader (September 2013). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ An Interview with Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Civilian Reader (September 2013). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Nightmare Magazine (January 22, 2014). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Interview: Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Nightmare Magazine (January 22, 2014). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden interviewed (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Alchemy Press (December 27, 2013). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden interviewed (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Alchemy Press (December 27, 2013). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ An Interview with Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Civilian Reader (September 2013). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Exclusive: Christopher Golden Talks Baltimore, Vampires, Mike Mignola And More (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Biff Bam Pop (July 5, 2012). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ An Interview with Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Civilian Reader (September 2013). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Exclusive: Christopher Golden Talks Baltimore, Vampires, Mike Mignola And More (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Biff Bam Pop (July 5, 2012). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Exclusive: Christopher Golden Talks Baltimore, Vampires, Mike Mignola And More (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Biff Bam Pop (July 5, 2012). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Tufts alumnus and best-selling author Christopher Golden talks writing with the Daily (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). The Tufts Daily (February 23, 2017). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ An Interview with Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Civilian Reader (September 2013). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Tufts alumnus and best-selling author Christopher Golden talks writing with the Daily (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). The Tufts Daily (February 23, 2017). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Author Interview: Christopher Golden on Soulless (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Cynthia Leitich Smith (January 4, 2019). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ An Interview with Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Civilian Reader (September 2013). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Christopher Golden (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ChristopherGolden.com. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

|

|

| {{{credit}}}

|

| Portrays:

|

Kevin Reikle

|

| Date of Birth:

|

September 18, 1963

|

| Date of Death:

|

Missing required parameter 1=month!

|

| Age:

|

62

|

| Nationality:

|

CAN CAN

|

|

|

@ BW Media

|

[{{{site}}} Official Site]

|

|

|

Warning: Default sort key "Heyerdahl, Christopher" overrides earlier default sort key "Stone, Christopher".

Christopher Heyerdahl (born September 18, 1963) is a Canadian actor who portrayed Kevin Reikle in Caprica.

Heyerdahl was born in British Columbia, Canada, and is of Norwegian and Scottish descent.[1] His father emigrated from Norway in the 1950s, and he is a first cousin once removed of famed Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl.[1][2] He is fluent in French and has starred in several French-language productions.[2]

Heyerdahl is a classically trained actor who honed his craft at Canada's Stratford Shakespeare Festival.[2] He has an extensive career in Canadian and American television, particularly within the science fiction genre.

Before his role on Caprica, he was well known to sci-fi fans for his multiple roles in the Stargate franchise. In Stargate: Atlantis, he played two prominent, recurring roles: the Athosian leader Halling, and the fan-favorite, duplicitous Wraith commander, "Todd".[3] Heyerdahl enjoyed the character's unpredictability and his complex relationship with Colonel Sheppard, calling it a "very questionable relationship" that was the best part of the role.[4] He felt Todd should always remain an unpredictable "X factor" in the series.[5]

His other notable genre roles include the demon Alastair in Supernatural, and the dual roles of Bigfoot and John Druitt in Sanctuary.[6] In The Twilight Saga, he played Marcus, an ancient vampire leader whose power is to sense the relationships between others. Heyerdahl viewed the Volturi not as simple villains, but as a necessary governing body, arguing, "Someone has to rule. Otherwise it would be a free for all."[7]

He gained further acclaim for his role as the antagonist Thor Gundersen, better known as "The Swede," in the AMC western series Hell on Wheels. Heyerdahl drew upon his Norwegian heritage for the role, using his father's accent as direct inspiration.[1] He considered the character's restrictive, high-collared costume a "gift" that was essential to embodying the character's rigid and controlled psychology.[8] He found the character's misnomer of 'The Swede' to be an authentic and "hilarious" detail, reflecting a real-world slight often felt by Norwegians, joking that "The Swedes have just got a better publicity agent."[1]

According to actress Magda Apanowicz in the podcast commentary for "Blowback," Heyerdahl was genuinely concerned that she might accidentally hit him for real during the scene where her character, Lacy Rand, attacks Reikle with a rifle.[9]