| [[File:|200px]]

|

| Role:

|

Director

|

| BSG Universe:

|

Galactica 1980

|

| Date of Birth:

|

November 10, 1927

|

| Date of Death:

|

July 5, 1985

|

| Age at Death:

|

57

|

| Nationality:

|

USA USA

|

[ Official Site]

|

| IMDb profile

|

Warning: Default sort key "Crane, Barry" overrides earlier default sort key "Van Dyke, Barry".

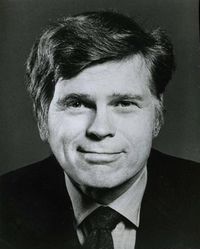

Barry Crane (born Barry Cohen; November 10, 1927 – July 5, 1985) was a prolific American television director and producer who directed two episodes of Galactica 1980: "Spaceball" and "The Night the Cylons Landed, Part II".[external 1] By profession a television director and producer, Crane was also the contract bridge expert who won more titles than anyone else in the history of the game at the time of his death.[external 2]

Early Career and Transition to Directing

edit

Born Barry Cohen in Detroit, Crane moved from the Detroit area to Hollywood in the mid-1950s for professional reasons and changed his name from Barry Cohen.[external 3] Before his tenure on Mission: Impossible and Mannix, Crane worked as a production manager at series such as Burke's Law at Four Star Productions.[commentary 1]

Crane served as associate producer for most of Mission: Impossibles run, and was promoted to producer in the show's final season.[commentary 2] He earned a reputation as Mission: Impossibles "human computer" for his exceptional ability to quickly break down complex scripts into filming schedules.[commentary 3] Producer Stanley Kallis, speaking to author Patrick J. White in 1991's The Complete Mission: Impossible Dossier, described him as "a walking computer" for this remarkable skill.[commentary 4] Crane also produced The Magician and was a producer on Mannix.[external 4]

Peak Directing Years

edit

By the mid-1970s, Crane had transitioned primarily to directing, working on various television series.[commentary 5] His directing credits included helming the final episode of Hawaii Five-O, "Woe to Wo Fat," in 1980.[commentary 6] Crane's extensive directing credits included episodes of major television series such as The Incredible Hulk, CHiPs, Dallas, Wonder Woman, Trapper John, M.D., The Love Boat, Fantasy Island, Police Woman, Police Story, and The Streets of San Francisco.[external 5]

Crane's work on Galactica 1980 represented his contributions to the Battlestar Galactica franchise. He directed "Spaceball" and "The Night the Cylons Landed, Part II" during the series' 1980 run.[external 6]

While maintaining his demanding television career, Crane simultaneously became the most dominant contract bridge player of his generation. According to the American Contract Bridge League (ACBL), he was "widely recognized as the top matchpoint player of all time"—the tournament format commonly played in private clubs.[external 7] Crane was "one of a small group of world champion bridge players whose presence enhanced many tournaments while they maintained active and highly respected careers outside of bridge."[external 8]

Crane's bridge career spanned almost four decades, beginning in the late 1940s when he won his first regional tournament.[external 9] In 1951, at age 23, his team finished second in the prestigious Vanderbilt Knockout Teams, and he became ACBL Life Master #325.[external 10] He was the winner in 1952 of the McKenney Trophy, awarded to the player winning the most master points in a year.[external 11]

In 1968, Crane overtook the late Oswald Jacoby as the career leader in master points, a position previously held only by Jacoby and Charles Goren.[external 12][external 13]

As an amateur in a game dominated in recent years by professionals, Crane outdistanced everyone. His career total of master points reached 35,000 a month before his death.[external 14] At the time of his death in 1985, he had accumulated 35,138 masterpoints, more than 11,000 ahead of any other players.[external 15] His nearest challenger had fewer than 24,000 masterpoints.[external 16]

Championships and Records

edit

Crane was invariably a contender for the McKenney title, and he won that title on five other occasions: 1967, 1971, 1973, 1975 and 1978.[external 17] He was second five times.[external 18] Crane won the McKenney Trophy six times total, and was runner-up six times. He exerted so much influence on the race that after his death it was renamed the "Barry Crane Top 500."[external 19]

His total number of titles was about 500, almost double that of his closest rivals.[external 20] Playing with one of his favorite partners, Kerri Shuman of Los Angeles, Crane won the World Mixed Pair title in 1978 in New Orleans.[external 21] At the 1978 World Championships, he and Kerri Shuman (now Sanborn) ran away with the World Mixed Pairs in a field loaded with international stars. This stunning victory, by more than five boards, further enhanced Crane's claim to the title of world's best matchpoint player.[external 22] The World Bridge Federation officially lists Barry Crane and Kerri Shuman as winners of the Mixed Pairs championship in 1978.[external 23]

He won 13 national titles, including 6 victories, a record, in the National Open Pairs.[external 24] His aggressive bidding style was particularly suited to pair events, in which Crane and a partner would face different opponents every 15 minutes.[external 25] In the Spring North American Championships in Montreal in 1985, his team finished second in competition for the Vanderbilt Trophy, a prestigious annual event that he never won.[external 26]

Despite his bridge addiction, Crane had an abiding passion for his work. It never bothered him when he couldn't go to a tournament, because his job was his prime interest.[external 27] He continued to play bridge with enthusiasm, traveling the country almost every weekend to compete in regional tournaments.[external 28] He usually could arrange his TV production schedule so he could attend most tournaments for a few days. A habitual weekend commuter, he said he would travel anywhere within flying distance for a regional and anywhere within driving distance for a sectional.[external 29]

Legacy and Recognition

edit

In recognition of his dominance and influence on the game, the ACBL renamed the annual McKenney Trophy to the Barry Crane Trophy following his death.[external 30] The trophy is awarded to the player who accumulates the most masterpoints in a single year. Crane was posthumously elected to the ACBL Hall of Fame in 1995 as a Grand Life Master.[external 31]

The British bridge writer S.J. Simon described Crane as a "natural" player. "Barry Crane was a Natural. We shall not see his like again," Simon wrote, according to an ACBL biography quoted by NBC News.[external 32]

The ACBL biography noted that "in many respects Crane was an A-1 ambassador and publicist for bridge all over North America. No one gave as many interviews to the media in as many different cities and towns."[external 33]

Murder and Investigation

edit

Barry Crane was found bludgeoned in the garage of his luxury town home Friday in Studio City, a neighborhood of Los Angeles, according to a report from the Associated Press.[external 34] His housekeeper discovered his body wrapped in bedding on the garage floor of his residence.[external 35] He had been beaten repeatedly with a large ceramic statue, and a telephone cord was wrapped around his neck, according to the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office.[external 36] Crane was 57 years old.[external 37]

Lt. Ron LaRue of the police said there was no apparent motive for the killing and no arrests had been made at the time.[external 38] Crane's Cadillac was stolen from the property and later recovered with forensic evidence.[external 39] Police were able to recover forensic evidence from the vehicle, including fingerprints and cigarette butts.[external 40]

The week of his murder, Crane had been playing daily in the annual Pasadena regional knockout teams bridge tournament. The Los Angeles Times reported at the time that his team won the tournament the day after his body was discovered.[external 41] Crane had survivors including two children, Sharilyn Cohen of Birmingham, Michigan, and Ben Crane of Ithaca, New York; and a brother, Elliot Cohen of Michigan.[external 42]

Cold Case Investigation

edit

The case remained unsolved for 34 years despite initial investigative efforts.[external 43] In 2006, and again in 2018, a detective from the Los Angeles Police Department's Robbery Homicide Division requested that evidence from the crime scene be retested using modern forensic techniques.[external 44]

After an attempt in July 2018, the Robbery Homicide Division received a forensic match to a suspect: Edwin Jerry Hiatt, who resided in North Carolina.[external 45] A fingerprint specialist matched a print from Crane's stolen car to Hiatt.[external 46] According to court documents cited by The News Herald, Hiatt's DNA matched cigarette butts recovered from the ashtray of Crane's stolen car.[external 47] The FBI tracked Hiatt through social media and conducted surveillance, collecting discarded cigarettes and a foam cup for DNA testing, according to CNN affiliate WSOC TV.[external 48]

Arrest and Prosecution

edit

Detectives traveled to Rutherford College, North Carolina, and interviewed Hiatt on March 8, 2019.[external 49] During the interview, Hiatt admitted to killing Barry Crane, according to the Los Angeles Police Department.[external 50]

On May 9, 2019, Edwin Jerry Hiatt was arrested by the FBI Fugitive Task Force in Burke County, North Carolina.[external 51] He was working at a Mercedes-Benz repair shop at the time of his arrest.[external 52] Hiatt was 18 years old at the time of Crane's murder in 1985.[external 53]

As he was being escorted to jail, Hiatt told reporters he had no clear memory of the killing, stating "I don't remember the guy until they told me his name, and then I didn't remember his picture."[external 54] When asked if he was involved in the murder, he responded, "Anything is possible back then because I was big into drugs."[external 55]

Hiatt was initially charged with one count of murder with a special allegation of using a deadly and dangerous weapon (a heavy decorative object) during the commission of the crime.[external 56] He pleaded not guilty in October 2019.[external 57]

Guilty Plea and Sentencing

edit

On October 7, 2021, Hiatt changed his plea and pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter as part of a plea agreement with the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Office.[external 58] The original murder charge was dismissed as part of the agreement.[external 59]

Along with the voluntary manslaughter charge, Hiatt admitted an allegation that he used a deadly weapon in the attack.[external 60] Superior Court Judge Eric Harmon immediately sentenced Hiatt, now 55 years old, to 12 years in state prison.[external 61]

Deputy District Attorney Beth Silverman, who prosecuted the case, called the killing "horrendous" and noted that "it took 36 years to bring Mr. Hiatt to justice."[external 62] Hiatt's attorney, Joshua Smart, told the judge that his client is religious and a "different human being" now, stating "Mr. Hiatt is here and obviously willing to accept punishment and accept responsibility."[external 63]

In a statement read in court by the deputy district attorney, Crane's daughter wrote that her father was an "exceptional man" who "suffered a horrific death," calling his killer "despicable."[external 64]

- ↑ Barry Crane (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane, 57, Expert in Bridge, Found Slain (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane Name Change (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane - Producer Credits (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Suspect In TV Director Barry Crane's Killing Pleads Guilty (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Deadline (October 7, 2021). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Galactica 1980 - Full Cast & Crew (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane - ACBL Hall of Fame (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). American Contract Bridge League. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ ACBL Hall of Fame - Barry Crane (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). FPAB. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane Career Start (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). FPAB. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane Life Master Achievement (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). FPAB. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane 1952 McKenney Trophy (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane Overtakes Jacoby (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane Becomes Top Masterpoint Holder (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). FPAB. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's Masterpoint Total (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's Final Masterpoint Total (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). FPAB. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's Nearest Competitor (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's McKenney Trophy Wins (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's McKenney Second Place Finishes (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane's Influence on Masterpoint Race (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). FPAB. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's Total Championships (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane Wins World Mixed Pairs (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane World Championship Victory (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). American Contract Bridge League. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ The Mixed Pairs (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). World Bridge Federation. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's National Championships (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's Playing Style (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's 1985 Vanderbilt Finish (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's Career Balance (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). American Contract Bridge League. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's Tournament Travel (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's Travel Habits (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). American Contract Bridge League. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane Top 500 History (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). American Contract Bridge League. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane Hall of Fame Induction (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). NBC News (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ S.J. Simon on Barry Crane (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). NBC News (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane as Bridge Ambassador (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). NBC News (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane Found Murdered (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane case: Arrest made 34 years after TV director's killing (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane Murder Method (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane Age (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ No Apparent Motive in 1985 (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane Stolen Vehicle (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Forensic Evidence in Crane Case (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's Final Tournament (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). NBC News (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Barry Crane Survivors (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Chicago Tribune (July 9, 1985). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Murder of prominent 1970s Hollywood director Barry Crane solved 34 years later (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ABC News (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Evidence Retesting in Crane Case (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ABC News (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ 2018 Forensic Match (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ABC News (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Fingerprint Match to Hiatt (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ DNA Evidence Links Hiatt (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). The New York Times via The Spy Command. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ FBI Surveillance of Hiatt (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Detectives Interview Hiatt (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ABC News (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Hiatt Confesses to Killing (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ABC News (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Edwin Hiatt Arrested (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). ABC News (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Hiatt's Workplace (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Hiatt's Age in 1985 (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Hiatt Claims No Memory (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Hiatt's Drug Statement (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Murder Charges Against Hiatt (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). CNN (May 10, 2019). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Suspect Enters Plea In 1985 Killing Of TV Director Barry Crane (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Deadline (October 7, 2021). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Suspect In TV Director Barry Crane's Killing Pleads Guilty To Lesser Charge (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Deadline (October 7, 2021). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Man Pleads Guilty to Killing TV Director (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). KFI AM 640. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Man pleads guilty to killing TV director in Studio City in '85 (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Daily News (October 8, 2021). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Hiatt Sentenced to 12 Years (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Deadline (October 7, 2021). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Prosecutor's Statement on Justice (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Deadline (October 7, 2021). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Defense Attorney Statement (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). KFI AM 640. Retrieved on November 4, 2025.

- ↑ Crane's Daughter's Victim Impact Statement (backup available on Archive.org)

(in English). Deadline (October 7, 2021). Retrieved on November 4, 2025.