| |||||

| |||||

| {{{credit}}} | |||||

| Portrays: | Greenbean | ||||

| Date of Birth: | September 16, 1949 | ||||

| Date of Death: | Missing required parameter 1=month! | ||||

| Age: | 76 | ||||

| Nationality: | |||||

| Related Media | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| @ BW Media | |||||

[ Official Site]

| |||||

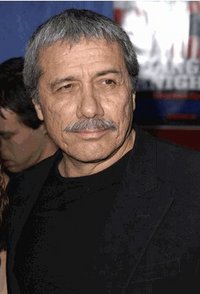

Ed Begley, Jr. (born 16 September 1949 in Los Angeles, California) is an American actor.

The son of actor Ed Begley, the junior Begley has a extensive filmography with credits in many television shows since the 1970s.

Nominated for an Emmy for his role as Dr. Victor Ehrlich in the 1988 TV medical drama, St. Elsewhere, Begley also appeared on the CW Network show, Veronica Mars.

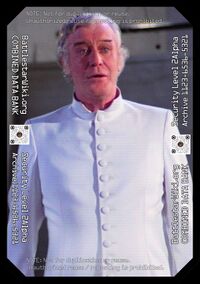

He also appeared as Henry Starling in the Star Trek: Voyager two-parter, "Future's End" and "Future's End, Part II".