Allan Miller

More actions

For other people with the same last name, see: Miller.

|

| |||||

| |||||

| {{{credit}}} | |||||

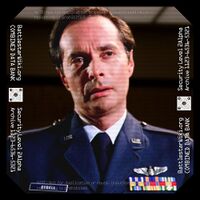

| Portrays: | Colonel Jack Sydell | ||||

| Date of Birth: | February 14, 1929 | ||||

| Date of Death: | Missing required parameter 1=month! | ||||

| Age: | 97 | ||||

| Nationality: | |||||

| Related Media | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| @ BW Media | |||||

Allan Miller (born February 14, 1929) is an American stage, film, and television actor who portrayed Colonel Jack Sydell in Galactica 1980. Miller is equally renowned as an accomplished director, acting teacher, playwright, and cultural institution founder.

Biography

editEarly Life and Military Service

editBorn on February 14, 1929, in Brooklyn, New York, Miller is the son of Benedict and Anna (née Diamond) Miller.[external 1] Miller served in the U.S. Army after World War II during the occupation of Japan. Noticing an advertisement in Stars and Stripes that was looking for performers, he began performing in shows to entertain the troops.[commentary 1]

Training and Early Career

editFollowing his military service, Miller studied with some of the most distinguished acting teachers of his generation. He trained with Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio, Uta Hagen at HB Studio, and Erwin Piscator at the Dramatic Workshop.[commentary 2] Miller spent the 1950s studying at the Actors Studio under Strasberg, becoming a member of the prestigious organization in his twenties.[commentary 3]

During his time at the Actors Studio, Miller's classmates included James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, and Paul Newman. Miller recalled that Monroe "emanated sadness" and that no one sat near her in class until one day he decided to socialize with her. When he approached, she "lit up and called me by name to ask if I'd like to sit with her." Miller discovered that Monroe had memorized almost everyone's name in the sessions.[commentary 4] Monroe planned to bike ride across the Brooklyn Bridge to take two recently born kittens from Miller's apartment in Brooklyn back to her hotel to care for them, but the hotel refused to let her bring them in.[commentary 5] Regarding James Dean, Miller noted that Dean was "very short sighted, and commented rarely, but when he did it was very pointed and pertinent."[commentary 6]

Miller did not make his television debut until 1967, when he appeared in an episode of the CBS soap opera The Edge of Night.[external 2]

Career

editActing

editFilm and Television

editNow retired from acting, Miller worked for decades as an actor, appearing in over two hundred films and television productions.[commentary 7] His last film was Bad Words (2013), directed by Jason Bateman.[external 3]

His film career included notable roles in Baby Blue Marine (1976), Two-Minute Warning (1976), Fun with Dick and Jane (1977), MacArthur (1977), Cruising (1980), Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984), and Brewster's Millions (1985).[external 4] Through these films, he shared screen time with such luminaries as Gregory Peck (MacArthur), Al Pacino (Cruising), and Richard Pryor (Brewster's Millions).[external 5]

Miller's television work was extensive, with his earliest spots appearing in primetime crime dramas including Starsky and Hutch and Kojak, science fiction series such as Galactica 1980 as the perpetually hapless Colonel Jack Sydell, and sitcoms including Soap (1980-1981).[external 6] He played Inspector Cramer in the television series Nero Wolfe on NBC.[commentary 8] Miller is perhaps best known on television for playing Harland Richards in the NBC soap opera Santa Barbara.[external 7]

Notable among Miller's television work was his experience on Barney Miller, where he appeared in four episodes. He described the experience as "like rehearsing a play every time," noting the terrific cast and guest stars and the hurried rehearsal schedule that sometimes went on until 3 AM.[commentary 9]

Stage Work

editMiller performed on stages across the country and on Broadway, appearing in dozens of plays.[commentary 10] His stage credits include Curve of Departure at South Coast Repertory, Awake and Sing at the Odyssey Theatre, Broadway Bound at La Mirada Theater, Three Views of the Same Object at Rogue Machine Theatre, and the title role of Willie Loman in Death of a Salesman at South Coast Rep.[external 8]

Most notably, Miller co-starred in the Broadway production of Broadway Bound and appeared in Brooklyn Boy by Donald Margulies, playing the role of Manny Weiss at the Biltmore Theatre in New York City.[external 9]

Directing

editMiller was the artistic director of the Back Alley Theatre, which he created and ran with his wife, Laura Zucker, from 1979 to 1989.[commentary 11] For his work at the Back Alley Theatre, he received the LADCC (Los Angeles Drama Critics Circle) Margaret Hartford Award for Distinguished Achievement.[commentary 12]

At the Back Alley, Miller directed more than a dozen productions, including Are You Now or Have You Ever Been... and The Fox, for which he received an LADCC award for direction.[commentary 13] He was also one of the primary plaintiffs in a landmark lawsuit between Actors' Equity Association and Los Angeles-based small theaters, focused on the Equity Waiver Plan.[external 10]

Other directing credits include The Fox Off-Broadway at the Roundabout Theatre and at the Berkshire Theatre Festival, Camping with Henry and Tom at the Westport Playhouse, and A Perfect Ganesh by Terence McNally (nominated for eight LADCC awards).[commentary 14] He has directed nine productions at the Odyssey Theatre, including Juno and the Paycock, This Lime Tree Bower, Taking Steps, and First Love.[external 11] He also directed Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? for the Actors Studio West.[commentary 15]

Playwriting

editMiller wrote the play The Fox, based on the D.H. Lawrence novella of the same name. He began looking for material to act that was not Chekhov, Arthur Miller, or Tennessee Williams, and re-read short stories he enjoyed, including Lawrence's The Fox.[commentary 16]

The Fox has been produced by theaters in Atlanta, Philadelphia, Seattle, Fort Worth, Austin, San Francisco, San Diego, and most of the fifty states, including the territory of Puerto Rico.[commentary 17] The play has been optioned internationally in France, Germany, Belgium, Hong Kong, Canada, and Argentina, and has toured England and Australia.[external 12] It has been translated into French, Spanish, German, and Chinese,[commentary 18] and has been published by Samuel French in an acting edition, Doubleday for the Fireside Book Club, and the California Arts Council's West Coast Plays.[external 13]

Teaching and Cultural Leadership

editActing Instruction

editPerhaps most impressive is the roster of acclaimed actors who have studied under Miller's direction. His students have included Barbra Streisand, Dustin Hoffman, Meryl Streep, Geraldine Page, Lily Tomlin, Sigourney Weaver, Peter Boyle, Rue McClanahan, Dianne Wiest, and Bruce Davison.[commentary 19]

Miller's relationship with Barbra Streisand began when she was only fifteen years old. At the request of his wife at the time, Anita Cooper, Miller gave Streisand a scholarship to one of his classes after having her to dinner. Streisand attended all his classes and became their live-in babysitter.[commentary 20] He coached Streisand from the time she was fifteen through the opening of Funny Girl on Broadway.[commentary 21] Streisand described Miller as "the person who changed her life," crediting him with helping her discover that life doesn't have to have "regimentation or meaningless boundaries."[commentary 22] Miller is prominently featured in Streisand's autobiography, My Name Is Barbra.[external 14]

With Meryl Streep at Yale, Miller recalled that her nickname on the faculty was "The Ice Queen"—brilliant but cold. He believed he was the first instructor to almost make her cry.[commentary 23]

In 1965, Miller was part of the inaugural program teaching acting for the federal agency HARYOU-ACT at the New Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, where he established an acting company of teenagers that included Antonio Fargas.[commentary 24]

Miller teaches acting privately and at colleges and professional schools, including Circle in the Square, the Actors Studio (where he has been a moderator as well as an instructor), Yale School of Drama, New York University's MFA professional program, the Focus Theatre in Dublin, and the International Actors group in Rome.[external 15] He continues to teach acting and coach privately, offering free weekly Zoom classes through his website.[external 16]

Miller's work as a master teacher is featured in the compilation book A New Generation of Acting Teachers, published by Penguin.[commentary 25]

Symphony Space Co-Founder

editIn 1978, Miller co-founded Symphony Space, a multi-disciplinary performing arts organization on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, with his neighbor and friend Isaiah Sheffer.[production 1] On January 7, 1978, Miller and Sheffer rented the decrepit Symphony Theater for $300 for a one-day event called "Wall to Wall Bach," a free 12-hour music festival featuring audience participation.[production 2]

The event was so successful that Miller and Sheffer immediately decided to lease the building and transform it into a permanent cultural venue.[production 3] Miller served as co-Artistic Director of Symphony Space alongside Sheffer for ten years, from 1978 to 1988.[production 4] Miller resigned as co-artistic director of Symphony Space in 1991.[production 5]

Author and Publications

editMiller is the author of A Passion for Acting: Exploring the Creative Process, now in its third printing and recently released digitally on Amazon.[commentary 26] He also created a DVD titled The Craft of Acting: Auditioning.[commentary 27]

Professional Associations

editMiller is a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and has served on the Board of Directors of the Screen Actors Guild.[commentary 28] He has been a panelist for the City of Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Department and the California Arts Council.[commentary 29]

Personal Life

editMiller has been married twice.[external 17] His first marriage lasted 18 years and produced two sons, Gregory and Zachary, and two grandsons.[external 18][commentary 30]

Miller met Laura Zucker in 1972 when she was 21 and he was 43. She was a graduate student studying acting at Yale, and he had been hired by the Yale School of Drama to coach the directing students on how to work with actors.[commentary 31] Miller recalled that he met Zucker shortly after separating from his first wife, and was not looking for a relationship but simply "someone to have dinner with before I went to see a student's show."[commentary 32] He noted that Zucker "was very generous to the other actors, and had no ego drive. There was a warmth about her."[commentary 33]

At the end of the 1972 academic year, they both left Yale and moved into an apartment together. The following year they moved to Los Angeles so Miller could pursue an acting career, driving cross-country with no air-conditioner and no radio in July.[commentary 34]

They were married in Beverly Hills, California, in the home of Zucker's sister. Due to a mistake involving a "fake rabbi" (who was actually a lawyer and friend of Zucker's brother-in-law), the couple uses two wedding dates: January 24 and 25, 1976, with January 25 being the legal date.[commentary 35] The marriage had to be finalized the next day when Zucker's uncle, George Zucker, then a Beverly Hills judge, noticed the certificate wasn't properly signed and performed a second ceremony at a small reception.[commentary 36]

As of 2018, Miller and Zucker had been married for over 42 years.[commentary 37] Miller reflected on their relationship: "I've become more flexible and honest. I stopped exaggerating or lying. I can count on her support... I learned we couldn't go to bed angry. If she was mad I couldn't sleep."[commentary 38] He noted that in the first couple of years, he thought Zucker might "get tired of being with an older guy," but added, "I have a young spirit. Somehow the life I was offering her was adventurous to her."[commentary 39] The couple walk together every morning or night, with Zucker sometimes "teasingly smack[ing] me across the chest to make sure I'm not drowsing along."[commentary 40]

Zucker works in Los Angeles as an arts management consultant at AEA Consulting.[commentary 41] The couple decided not to have children together, though Miller was completely open to it.[commentary 42]

References

editProduction History

edit- ↑ History (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Symphony Space (July 22, 2025). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ An Unknown History of Symphony Space (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). I Love the Upper West Side (November 20, 2023). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ History (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Symphony Space (July 22, 2025). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Board & Staff (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Symphony Space (May 1, 2018). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Symphony Space records (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). New York Public Library Archives. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

External Sources

edit- ↑ Allan Miller Biography (1929-) (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Film Reference. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller Movies & TV Shows List (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller - Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller - Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller Movies & TV Shows List (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller Movies & TV Shows List (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller Movies & TV Shows List (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller - Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Wikipedia (September 26, 2025). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller - Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller - Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller - Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller - Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller - Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller - Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). IMDb. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Wikipedia (September 26, 2025). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller Biography (1929-) (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Film Reference. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

Commentary and Interviews

edit- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller: Actor's Studio, Marilyn Monroe, Barbra Streisand, The Fox & More… (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). RingSide Report. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller Remembers Marilyn … and Her Feline Friends (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The Marilyn Report (July 5, 2022). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller Remembers Marilyn … and Her Feline Friends (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The Marilyn Report (July 5, 2022). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller Remembers Marilyn … and Her Feline Friends (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The Marilyn Report (July 5, 2022). Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller: Actor's Studio, Marilyn Monroe, Barbra Streisand, The Fox & More… (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). RingSide Report. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller: Actor's Studio, Marilyn Monroe, Barbra Streisand, The Fox & More… (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). RingSide Report. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller: Actor's Studio, Marilyn Monroe, Barbra Streisand, The Fox & More… (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). RingSide Report. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller: Actor's Studio, Marilyn Monroe, Barbra Streisand, The Fox & More… (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). RingSide Report. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller - The Person Who Changed Barbra Streisand's Life (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Hollywood Actors Network. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Allan Miller: Actor's Studio, Marilyn Monroe, Barbra Streisand, The Fox & More… (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). RingSide Report. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Biography (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). Allan Miller Official Website. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.

- ↑ Alix Strauss (August 8, 2018). Age Difference Didn't Matter Then, Or Now (backup available on Archive.org) (in English). The New York Times. Retrieved on November 3, 2025.